Intermittent fasting for metabolic health

In our modern world, a growing number of individuals grapple with metabolic health issues, often feeling trapped in a cycle of fluctuating energy levels, weight gain, and overall decreased vitality.

Traditional diets and health regimens, while offering temporary fixes, often fail to address the root cause. This leaves many feeling frustrated, constantly battling their metabolism instead of having it work for them, leading to a cascade of health complications and a diminished quality of life.

Enter intermittent fasting – a time-tested approach that focuses not on what you eat, but when you eat. By aligning our eating patterns with our body's unique physiology and natural circadian rhythm, intermittent fasting offers a promising avenue to reset our metabolic health, paving the way for increased energy, sustainable weight loss, and a renewed sense of well-being.

Intermittent fasting is an increasingly popular method of eating that has various proposed benefits. While intermittent fasting (IF) seemed to initially gain popularity as a weight loss method, research is showing that the potential benefits go well beyond weight management (1). This article will explore the mechanisms by which IF works and some benefits and potential risks of practicing this eating style.

There is more than one way to practice IF, but all forms involve abstaining from calorie-containing food and beverages for a specified amount of time. The focus of IF is on when you eat rather than what or how much you eat. The different methods of IF include:

Fasting occurs every day within variable hours. The duration of the fasting time varies from person to person but is usually between 12 and 16 hours (2). This tends to be the easiest and most repetitive method of IF to follow.

Examples include:

Alternate-day fasting involves fasting for 24 hours every other day. On non-fasting days, there are no restrictions on what you can and cannot eat.

Two days of the week are significantly low in calories.

But what impact do the different types of fasting have on metabolic health?

When talking about intermittent fasting and the impact it can have on your health, it can be helpful to understand the physiology of what exactly is happening in the body during times of fasting. Simply put, IF alters energy metabolism by shifting the body from glucose to fat burning.

Let’s dive in to learn more:

During your fed state, your body is still digesting and absorbing the food you have recently eaten. Carbs from your food are converted into glucose for energy for the body’s cells. At this metabolic stage, the body does two things:

Over the next few hours, the body completes the breakdown of carbs into glucose. Blood sugar levels start to drop as the glucose from the food eaten is now mostly used or stored.

The body requires a continuous energy supply, but when food is unavailable, it lowers insulin levels and releases another hormone, glucagon. This hormone prompts the liver to convert stored glycogen into glucose to stabilize blood sugar levels, a process known as glycogenolysis.

After 8-12 hours of eating, the glucose from the food consumed has mostly been utilized or stored, leading to a drop in blood sugar levels.

Without available food and the need to sustain energy, the body decreases insulin levels and releases glucagon hormone. This hormone facilitates the conversion of liver-stored glycogen into glucose to stabilize blood sugar levels, a process termed glycogenolysis. Since this metabolic function continues to depend on glucose.

When fasting over 12 hours, the body continues to produce glucose for energy. However, with glycogen stores running low, it derives glucose from alternative sources.

This process is termed gluconeogenesis, with "neo" meaning "new." In this process, the liver generates new glucose from lactate and glycerol molecules, both of which are byproducts of metabolic processes not associated with carbohydrate metabolism. Lactate and amino acids are produced from muscle protein breakdown. This is a key reason why prolonged fasting can lead to muscle loss.

As the fasting period prolongs, the body increasingly depends on gluconeogenesis to meet its glucose requirements. At the same time, the body primarily derives energy from a breakdown of fat and the utilization of ketone bodies, entering a state called ketosis.

However, if fasting persists for an extended period, gluconeogenesis might begin to break down muscle tissue to sustain blood glucose levels, potentially leading to adverse health effects.

If the fasting extends more than your body's ability to adapt to fat burn, fasting can trigger a spike in cortisol and stress response, switching your body back into a carb burn state.

There are several proposed benefits of intermittent fasting, all of which are strongly correlated with the reduction in inflammation and cellular autophagy that is seen in IF (2).

Clinical studies have also shown that fasting has multiple benefits for your health:

One of the most challenging parts of traditional diets that promote weight loss can be reducing caloric intake. Unlike most calorie-restricted diets, studies have shown that IF can result in weight loss without restricting your calorie intake (2,4). A recent systematic review of over 27 trials found there to be an average body mass reduction of ~4% (5). This review also found that symptoms of hunger either remained stable or decreased, making it easier to sustain weight loss (5).

Although the benefits of IF seem independent of calorie reduction, some studies have found that IF may result in an unintentional 20% reduction in calories (2). This reduction of calories is likely from the reduction in body fat, which impacts some of the hormones that control hunger, including leptin and adiponectin (3). With a decrease in appetite, IF may make it easier to consume fewer calories without feeling hungry all the time (6).

Lastly, studies found there to be minimal weight regain after you stop IF (3). This makes IF a more promising method for sustainable weight loss as most traditional diets result in weight regain of at least the amount of weight originally lost, if not more.

Fasting helps lower insulin levels which enables fat-burn activation. It also improves mitochondrial function making your cells more efficient at burning fat. Insulin sensitivity helps to improve body composition by enabling cells to use carbs more effectively rather than store them as fat.

Studies have shown that for individuals with type 2 diabetes, IF can result in lower hemoglobin A1c (~3-month average of blood sugar levels) and fasting levels of both glucose and insulin (1, 3).

This benefit is believed to be achieved through the metabolic switching that occurs between the fed and fasting state and the reduction of inflammation and cholesterol (1).

IF can improve blood lipid levels, meaning it helps lower total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides in both overweight and non-overweight individuals. This is likely partially due to the anti-inflammatory effects of IF and the metabolic shift that results in less accumulation of triglycerides in the liver (1). By managing these levels, your body can protect itself against multiple diseases like diabetes, cancer, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome.

Like most things in the world of nutrition, the use of IF may not be right for everybody. Some commonly reported negative side effects of IF to look out for include hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), dizziness, and weakness.

If you are somebody with type 2 diabetes taking antidiabetic medications, the risk for hypoglycemia is even higher.

Additionally, any amount of weight loss can put an individual at risk for muscle wasting. This makes it essential for those practicing IF to ensure adequate protein intake. This can prevent several health risks and the slowing of metabolism efficiency.

Lastly, IF is not recommended for individuals with significant hormonal imbalances, pregnant and breastfeeding women, children, older adults, individuals with an active or previous eating disorder, and those with a compromised immune system (3).

Incorporating fasts into your lifestyle can be a great addition to your journey to better metabolic health. However:

Before jumping into IF, below are some precautions, steps, and tools that you can use to be better prepared before starting this process.

It is important to note that for the benefits of IF to be sustained, they must be accompanied by ongoing lifestyle and behavioral habits that support optimal health.

As mentioned above, one of the risks of IF could be loss of muscle mass. Muscle mass is more metabolically active than fat tissue, which means a reduction in muscle mass can result in a reduction of metabolic output. To reduce the risk of losing muscle mass, ensure that you are consuming adequate protein and incorporating resistance training regularly.

Additionally, it is best to consume nutrient-dense foods while practicing IF. Avoid highly processed foods and focus on whole foods, including fruits, vegetables, proteins, and grains.

Not everybody will react to intermittent fasting the same. This is where the use of the Lumen device can be helpful for you to determine your personal optimal fasting window. Read more about finding your personalized fasting window here.

Specific metabolic advantages are linked to certain times of the day. Studies indicate that our body is better equipped to process food during daylight hours. Factors such as insulin sensitivity, beta cell function, and the thermic effect of food tend to peak in the morning and afternoon, waning by evening.

Our metabolism is intertwined with our circadian rhythm—our internal clock that aligns with the sun's rise and set. This rhythm dictates when certain enzymes and hormones operate most efficiently.

Given that our metabolic efficiency is heightened during the day, initiating your fast in the evening (around 6pm to 9pm) is recommended to leverage its benefits fully. It's ideal to confine food consumption to an 8-hour window and certainly not exceed 12 hours.

Start by establishing a baseline with your Lumen: take a “before sleeping” measurement and follow it up with your usual fasted morning measurement. Then, pick one of these strategies:

These strategies will help you understand and optimize your fasting routine.

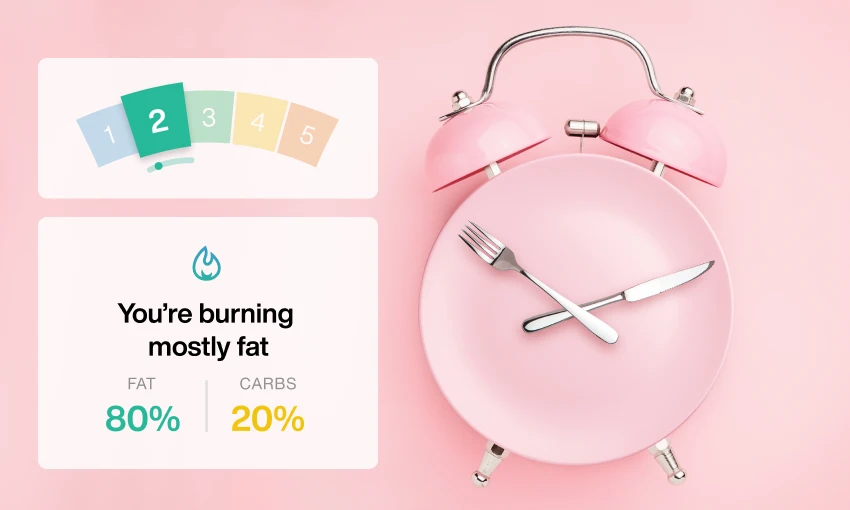

Fasting is considered to be successful when the metabolism adapts to a carb-depleted state and starts to burn fat. A fast can also be successful if there is a trend toward using more fats and less carbs for energy.

Successful fasting is determined based on:

A fast is successful when you fast up to your personal fasting capacity. Fasting capacity is when your metabolism adapts to a fasted state by achieving or maintaining more fat burn and less carb burn.

Around 30% of your daily water needs come from the foods you eat. During fasting, when food consumption is paused, it becomes imperative to maintain hydration—aiming for a minimum of 2.5 liters of water daily.

Further, it's prudent to exercise caution with caffeine and artificial sweeteners. Caffeine, apart from being a diuretic that could dehydrate you, can alter your metabolic trajectory favoring carbohydrate metabolism.

It's also worth noting that caffeine sensitivity varies among individuals. In certain cases, its consumption can elevate cortisol and adrenaline, inducing a stress-like response. This can inadvertently shift your body towards carbohydrate metabolism, potentially interrupting the fasting state.

Lumen helps you fast more effectively and avoid stress on your body by optimizing your fasting capacity. Personalizing your fasting schedule will help you find the sweet spot.

You can easily track your fasting capacity by measuring your fast. By taking measurements throughout your fast, you can ensure you don't elicit a stress response and switch back into a carb usage state.

When our body enters a state of stress, the benefits of fasting drastically decrease. Rather than trying to "push through it", as always, it's best to listen to your body and safely end your fast.

Lumen tells you when your fast starts to put your body into stress mode and that you should stop your fast. By taking fasting measurements for several hours after you wake up you can see how your body moves through the fasting stages and know if you’ve missed your sweet spot.

If you experience any of the following symptoms, you should take a measurement:

A shift toward more carb usage and less fat usage (i.e. a Lumen level 2 to a Lumen level 3) may be an indicator that your body has entered into a state of stress.

At this point, you may want to considered ending your fast.

A personalized approach to intermittent fasting has the potential to result in weight loss, improved lipid and glucose levels, and lower inflammation. It is important to note that every individual will respond differently, and intermittent fasting is not right for everybody.

Remember that there are several different ways to practice intermittent fasting. There is no one-size-fits-all method, and the correct method will depend on your personal health history. Before making any changes to your diet, please consult with your healthcare professional.

Use Lumen to gain greater insight into your personal optimal fasting window for you and how you personally respond to periods of intermittent fasting.

It's a popular myth that intermittent fasting slows your metabolism, but it actually has the opposite effect. Researchers discovered that fasting for short periods of time, such as the 16:8 strategy, can boost your metabolism.

According to an NLH study (7), a three-day fast can boost your metabolism by 14%. Researchers believe that a spike in norepinephrine, which helps make more fat available for burning, is the source of the metabolic increase. While a three-day fast may appear excessive, a milder fast can achieve the same fluctuation in norepinephrine. According to research, even 12-hour fasts boost metabolic processes and aid in weight loss.

1. Song DK, Kim YW. Beneficial effects of intermittent fasting: a narrative review. J Yeungnam Med Sci. 2023 Jan;40(1):4-11. doi: 10.12701/jyms.2022.00010. Epub 2022 Apr 4. PMID: 35368155; PMCID: PMC9946909.

2. Mandal S, Simmons N, Awan S, et al. Intermittent fasting: eating by the clock for health and exercise performance. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2022;8:e001206. doi:10.1136/

3. Vasim I, Majeed CN, DeBoer MD. Intermittent Fasting and Metabolic Health. Nutrients. 2022; 14(3):631. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030631

4. Cienfuegos S, Corapi S, Gabel K, Ezpeleta M, Kalam F, Lin S, Pavlou V, Varady KA. Effect of Intermittent Fasting on Reproductive Hormone Levels in Females and Males: A Review of Human Trials. Nutrients. 2022 Jun 3;14(11):2343. doi: 10.3390/nu14112343. PMID: 35684143; PMCID: PMC9182756.

5. Welton S, Minty R, O'Driscoll T, Willms H, Poirier D, Madden S, Kelly L. Intermittent fasting and weight loss: Systematic review. Can Fam Physician. 2020 Feb;66(2):117-125. PMID: 32060194; PMCID: PMC7021351.

6. Harvey J, Howell A, Morris J, Harvie M. Intermittent energy restriction for weight loss: Spontaneous reduction of energy intake on unrestricted days. Food Sci Nutr. 2018 Feb 21;6(3):674-680. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.586. PMID: 29876119; PMCID: PMC5980333.

7. Zauner C, Schneeweiss B, Kranz A, Madl C, Ratheiser K, Kramer L, Roth E, Schneider B, Lenz K. Resting energy expenditure in short-term starvation is increased as a result of an increase in serum norepinephrine. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000 Jun;71(6):1511-5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1511. PMID: 10837292.

Marine is a registered dietitian (RD) with extensive experience in clinical nutrition and a deep passion for well-being, health, and metabolism. With her background as a clinical dietitian and private practice owner, Marine has helped patients from diverse backgrounds improve their health through personalized nutrition. Currently, Marine serves as a customer success nutritionist at Lumen, where she provides expert nutrition support to clinics using Lumen’s technology to enhance their clients’ metabolic health. Marine is dedicated to empowering individuals to improve their relationship with food and achieve their health goals.