Intermittent fasting for women: Strategies for success

There’s no one-size-fits-all fasting window

In recent years, intermittent fasting has emerged as a trending and widely implemented regimen, with many experts in the scientific community pointing to its advantages, including weight loss and improvements in dyslipidemia and blood pressure [1].

While intermittent fasting can be effective for people looking to improve their health and well-being, there’s no one-size-fits-all approach. Women have distinctive hormonal and metabolic fluctuations that are important to consider when fasting. Measuring your metabolism enables you to find your optimal fasting window. It also helps you understand how your hormonal fluctuations might be affecting whether your mitochondria, your cells’ powerhouses, lean toward burning fats or carbs for fuel and how that plays into how long you should fast.

Let’s find out more!

“I was over-fasting for a woman of my age, thinking that the more you fast, the more you'll get into fat burn. However, all I was doing was putting my body under stress until I found Lumen.”

Amanda S., Lumen user

The physiology behind intermittent fasting and metabolic flexibility

Let’s take a closer look at what happens in your body when you intermittent fast.

The phases of a fast

When fasting, the body shifts from using glucose as a primary energy source in the fed state to glycogen, the storage form of carbs, and finally, stored body fat.

In the early phases, blood sugar levels drop, lowering insulin and the satiety hormone leptin. This reduction in insulin can help improve insulin sensitivity and potentially decrease the risk of developing type 2 diabetes [2].

To prevent blood glucose from dropping too low, glucagon is released. These changes stimulate glycogen breakdown to produce energy and keep your blood sugar levels in a healthy range [1].

When glycogen levels are depleted, the mitochondria switch to burning fats for fuel. The process known as lipolysis, causes triglycerides from fat cells to be broken down into smaller molecules that can be used as a fuel source, which helps your body practice metabolic flexibility. Depleted glycogen also leads to mitochondrial biogenesis which strengthens your metabolism.

What happens when you overextend your fast?

There is such a thing as fasting for too long. Overextending a fast can cause the body to release stress hormones, such as cortisol, in response to the perceived lack of energy intake.

These stress hormones can push the body into a state of carbohydrate metabolism, where it prioritizes burning carbohydrates over fats for energy. This shift arises from the body’s attempt to preserve fat stores if overextended fasting continues.

Cortisol, the primary stress hormone, increases glucose production by stimulating gluconeogenesis, a process in which the liver creates glucose from non-carbohydrate sources, such as amino acids from muscle protein breakdown.

Preserving muscle mass is especially important because they’re filled with mitochondria and glycogen, the storage form of carbs. The more muscle you have, the more energy you can burn at rest. Increased glycogen storage also ensures less glucose will be stored as fat when consuming carbs.

Avoiding muscle breakdown is especially important for menopausal women because sarcopenia, a decline in muscle mass, increases with age and during menopause [3].

“Lumen is an eye-opener. Use this tool to fuel your body the way it needs to help you succeed with your own goals. We’ve got this!”

Kait, 46, Chicago

The connection between women’s hormonal fluctuations and metabolism

Lumen’s latest research study [4] identified a distinct rhythmic pattern of CO₂ levels during the different phases of the menstrual cycle. CO₂ levels were significantly higher during the follicular phase leading up to ovulation, indicating more carb burn; whereas CO₂ was lower in the luteal phase, pointing to increased fat burn.

Lumen’s study also indicated higher morning CO₂ levels for menopausal women not using HRT compared to those with HRT. This suggests a decline in metabolic flexibility as a factor of hormonal changes, as healthy, well-rested mitochondria should burn fat in the morning after a fasted night.

Lumen can identify these metabolic shifts in your breaths over time and provide recommendations to support your hormonal rhythms. Such insights can give you a sense of understanding and empower you to make smart choices, especially when your mood, body, or cravings may feel out of balance.

“Fasting is a great tool if the timing is personalized. Women have different physiological responses, health conditions, and lifestyle factors that influence the effectiveness and safety of intermittent fasting regimens.”

Marine Melamed, R.D. at Lumen

Strategies from intermittent fasting experts

Cynthia Thurlow, NP and author of “Intermittent Fasting Transformation,” says part of setting up an intermittent fasting plan is determined by whether you have a monthly cycle or are in perimenopause or menopause.

“Your metabolism speeds up and slows down predictably across the month. Because of this, it’s important to change what you eat, do intermittent fasting, and increase the intensity of your workouts accordingly. All of these actions optimize your metabolism,” says Cynthia.

Dr. Mindy Pelz, author of “Fast Like a Girl,” explains that calorie restriction can negatively affect progesterone levels, the female hormone that peaks in the luteal phase. She adds that avoiding longer fasts during days 19-28 of your cycle can help keep your progesterone levels healthy [5]. Moreover, Cynthia doesn’t recommend fasting during the five to seven days preceding your menstrual cycle as it may unknowingly deplete nutrients and hormones necessary in the follicular phase. Dr. Pelz explains that it’s important to avoid longer fasts during this cycle phase because fasting is a type of hormetic stress. When the stress hormone cortisol increases, progesterone levels drop [6,7].

Dr. Pelz says your body is better equipped to handle hormetic stress in the follicular phase, the first half of the menstrual cycle, so many women can fast for longer then. In the follicular phase, cortisol levels are generally naturally higher, which can contribute to feeling more energetic and alert. This is a natural response of your body preparing for ovulation [8].

When it comes to menopause, Dr. Pelz says you can fast with few restrictions because of fewer hormonal fluctuations. However, she adds that women 55+ should be mindful of keeping hormone levels balanced by having at least one non-fasting carb reload day per week.

It’s also important to measure your metabolism throughout the fast to avoid muscle breakdown, which is already a process in play with aging [3].

With all these hormonal fluctuations, it’s important to find your ideal fasting window, which we discuss in detail below.

Finding your optimal fasting window

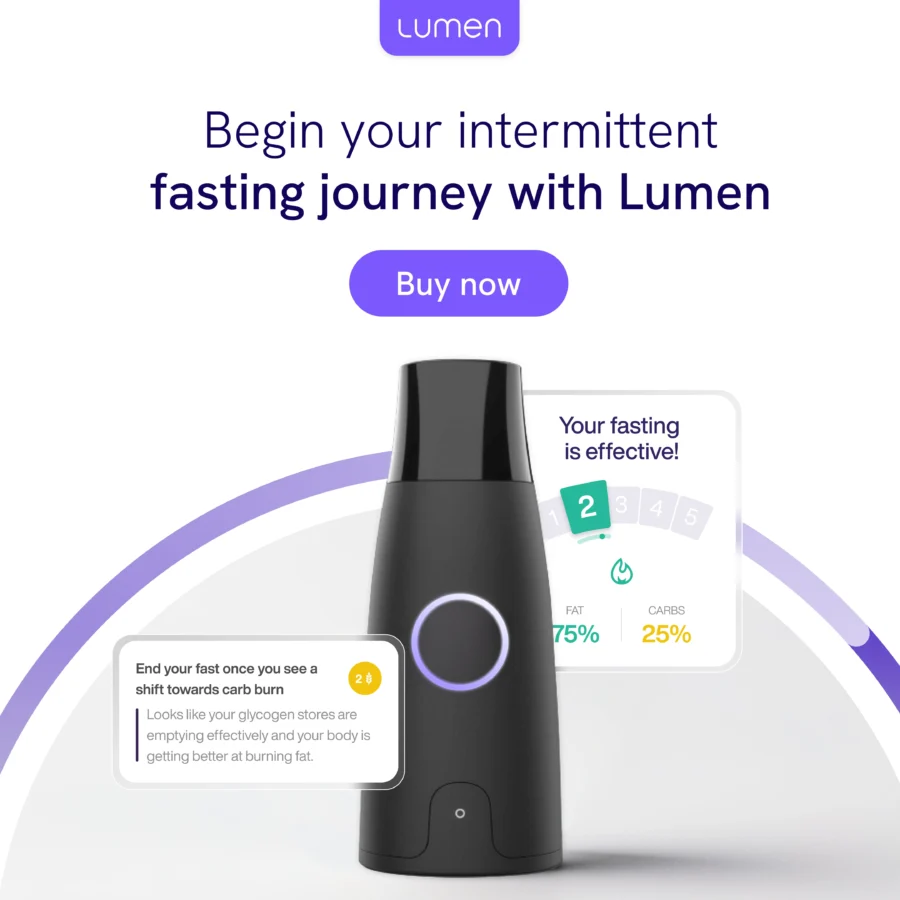

You can find your ideal fasting window by measuring your metabolism throughout your fast. For example, if you measure your metabolism after 12 hours of fasting and find you’re burning fats, try extending your fast and measuring your metabolism every 1-2 hours to determine what your mitochondria are burning for energy.

If you continue burning fat, this may indicate your glycogen stores are emptying and your fast is effective. If you’ve shifted back to carb burn, then you’ve passed your fasting sweet spot. That’s a sign to end your fast and eat something nutritious.

These insights are also helpful for eumenorrheic, perimenopausal, and menopausal women to understand their propensity for carb-burn and fat-burn in relation to hormonal changes and why they might be burning more carbs or fats on certain days. Because women experience a lot of hormonal variance, optimal fast times will change frequently, which is why it’s crucial to measure your metabolism throughout a fast and ensure your efforts don’t go to waste.

“I found that when I fasted past 16 hours, my Lumen levels started to increase. This is my body signaling that it’s going into stress mode. Without the biofeedback, I would never have known.”

Susan, 45, California

Frequently asked questions

What affects metabolic flexibility during a fast?

Several factors affect your mitochondria’s ability to switch between carb and fat burn while fasting, including:

- Length and timing of your fast

- Glycogen storage at the start of your fast

- Activity level during fasting

- Stress levels

- Sleep quality

- Monthly cycle and hormone balance

- Medications, diseases, and illnesses

What are popular intermittent fasting plans?

Intermittent fasting (IF) involves alternating eating and fasting for a certain period. Some of the most common methods include the 16:8 method, alternate-day fasting, and fasting-mimicking diets [9].

16:8 method: Fasting for 16 hours and eating within an 8-hour window.

The 5:2 method: Fasting two days a week through reduced caloric intake and eating at maintenance for the other five.

Alternate-day fasting (ADF): The ADF regimen consists of a fasting day, alternated with a day when people can eat as desired, called an ad libitum eating day [10, 11].

What are best practices for time-restricted eating or fasting with Lumen, specifically for women?

Measure your metabolism throughout your fast for personalized recommendations. Begin by measuring your metabolism when you first wake up to establish a baseline and determine whether you’re burning carbs or fats for fuel.

Continue measuring your metabolism every hour. The goal is to remain at level 1 or 2, which indicates fat burn. During a fast, your mitochondria should be burning fat for fuel. When you shift towards carb burn (level 4 or 5), this indicates you should break your fast, as your glycogen stores are getting critically low and leading your body to break down muscle for energy.

Do I need to follow a specific fasting plan?

Not at all. Lumen helps you customize your fast day by day and lets you see whether fasts you’re already doing, like 16:8 or OMAD, are working in your favor.

What are the drawbacks of overfasting?

Overfasting can lead to muscle breakdown, low energy, fatigue, irritability, and increased cravings. Measuring your metabolism during a fast helps you avoid that by finding your fasting sweet spot.

How does metabolic flexibility improve my health?

Metabolic flexibility refers to how efficiently your mitochondria switch from burning carbs or fats for fuel, depending on their availability and your body’s needs.

Being metabolically flexible can be important for disease prevention weight management, improved insulin sensitivity, higher energy levels, better sleep, and even longevity.

Does Lumen have any research on fasting?

Yes. Lumen’s intermittent fasting study involving 48,058 users revealed that Lumen’s sensitivity to variations in carb intake, fasting duration, BMI, and gender enables it to account for individual differences and assist users in optimizing their fasting routines. The study suggests that Lumen could be a valuable tool for monitoring the metabolic effects of various fasting regimens, which can assist in weight loss. Read the peer-reviewed paper.

Help your fast work with you, not against you

Everyone’s metabolism is unique, and your mitochondria’s ability to switch between carbs and fats as energy sources might differ, especially with hormonal fluctuations.

Real-time metabolic biofeedback can help you pinpoint your optimal fasting window, understand how your hormonal fluctuations might affect your carb-burn and fat-burn potential, and identify whether you are over-fasting and potentially hindering your progress toward your health goals.

References

- Vasim, I., Majeed, C. N., & DeBoer, M. D. (2022). Intermittent Fasting and Metabolic Health. Nutrients, 14(3), 631. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14030631

- Sutton, E. F., Beyl, R., Early, K. S., Cefalu, W. T., Ravussin, E., & Peterson, C. M. (2018). Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even without Weight Loss in Men with Prediabetes. Cell metabolism, 27(6), 1212–1221.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.04.010

- Messier, V., Rabasa-Lhoret, R., Barbat-Artigas, S., Elisha, B., Karelis, A. D., & Aubertin-Leheudre, M. (2011). Menopause and sarcopenia: A potential role for sex hormones. Maturitas, 68(4), 331–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.01.014

- Cramer, T., Yeshurun, S., & Mor, M. (2024). Changes in Exhaled Carbon Dioxide during the Menstrual Cycle and Menopause. Digital biomarkers, 8(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1159/000539126

- Williams, N. I., Reed, J. L., Leidy, H. J., Legro, R. S., & De Souza, M. J. (2010). Estrogen and progesterone exposure is reduced in response to energy deficiency in women aged 25-40 years. Human reproduction (Oxford, England), 25(9), 2328–2339. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deq172

- Herrera, A. Y., Nielsen, S. E., & Mather, M. (2016). Stress-induced increases in progesterone and cortisol in naturally cycling women. Neurobiology of stress, 3, 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2016.02.006

- Kouda, K., & Iki, M. (2010). Beneficial effects of mild stress (hormetic effects): dietary restriction and health. Journal of physiological anthropology, 29(4), 127–132. https://doi.org/10.2114/jpa2.29.127

- Kulzhanova, D., Turesheva, A., Donayeva, A., Amanzholkyzy, A., Abdelazim, I. A., Saparbayev, S., Stankevicius, E., Omarova, A., Balmaganbetova, F., Isayev, G., Bimagambetova, K., Batyrova, T., & Samaha, I. I. (2023). The cortisol levels in the follicular and luteal phases of the healthy menstruating women: a meta-analysis. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences, 27(17), 8171–8179. https://doi.org/10.26355/eurrev_202309_33577

- Soliman G. A. (2022). Intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating role in dietary interventions and precision nutrition. Frontiers in public health, 10, 1017254. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1017254

- Tinsley, G. M., & La Bounty, P. M. (2015). Effects of intermittent fasting on body composition and clinical health markers in humans. Nutrition reviews, 73(10), 661–674. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuv041

- Elortegui Pascual, P., Rolands, M. R., Eldridge, A. L., Kassis, A., Mainardi, F., Lê, K. A., Karagounis, L. G., Gut, P., & Varady, K. A. (2023). A meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness of alternate day fasting, the 5:2 diet, and time-restricted eating for weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.), 31 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.23568

Disclaimer

Everyone has different physiological needs, health conditions, and lifestyle factors that can affect their intermittent fasting regimens. Before you begin fasting, it’s best to consult a healthcare professional or nutrition expert to help determine the optimal fasting approach for your specific needs.

Digital download

Digital download