Syncing exercise and nutrition with your monthly cycle

When we think of our menstrual cycle, our minds might jump to cramps, bloating, cravings, and low energy. But there’s actually a lot more going on.

As a woman, you know that your monthly cycle may impact many aspects of your life. But, what if you could understand more about your monthly cycle and hormones and use this knowledge to adjust your lifestyle habits to work in sync with your physiology and metabolism?

The good news is, you can!

By understanding your cycle and making some simple adjustments, you can work with your body, not against it.

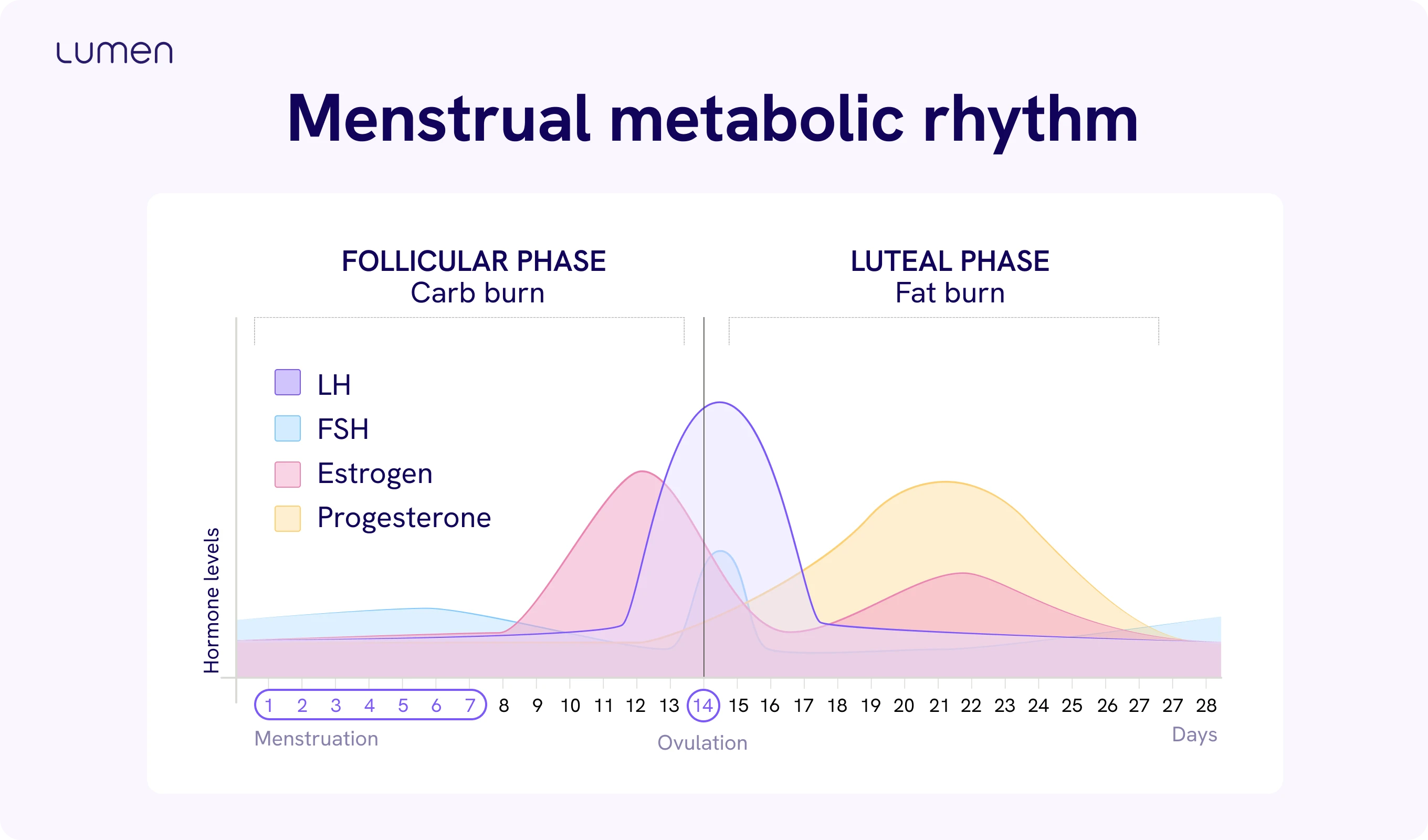

A woman’s metabolism changes throughout the month in distinct phases. Hormones play a crucial role in regulating metabolism [1,2], and the menstrual cycle can affect how the mitochondria, your cells’ powerhouses, produce energy from carbs and fats [3].

Lumen’s research [3] has identified changes in CO₂ levels in each monthly cycle phase. CO₂ is a fundamental marker of metabolic activity in the human body and provides valuable insights into physiological processes [4]. Higher CO₂ levels indicate carb burn, while lower CO₂ levels point to fat burn.

In the follicular phase – the first half of the monthly cycle leading up to ovulation – estrogen rises and progesterone is low, causing higher exhaled CO₂. In the luteal phase following ovulation, as progesterone increases and estrogen drops, exhaled CO₂ is lower [3].

Becoming aware of these shifts during your monthly cycle can help you understand your body and sync your nutrition and fitness to your physiology.

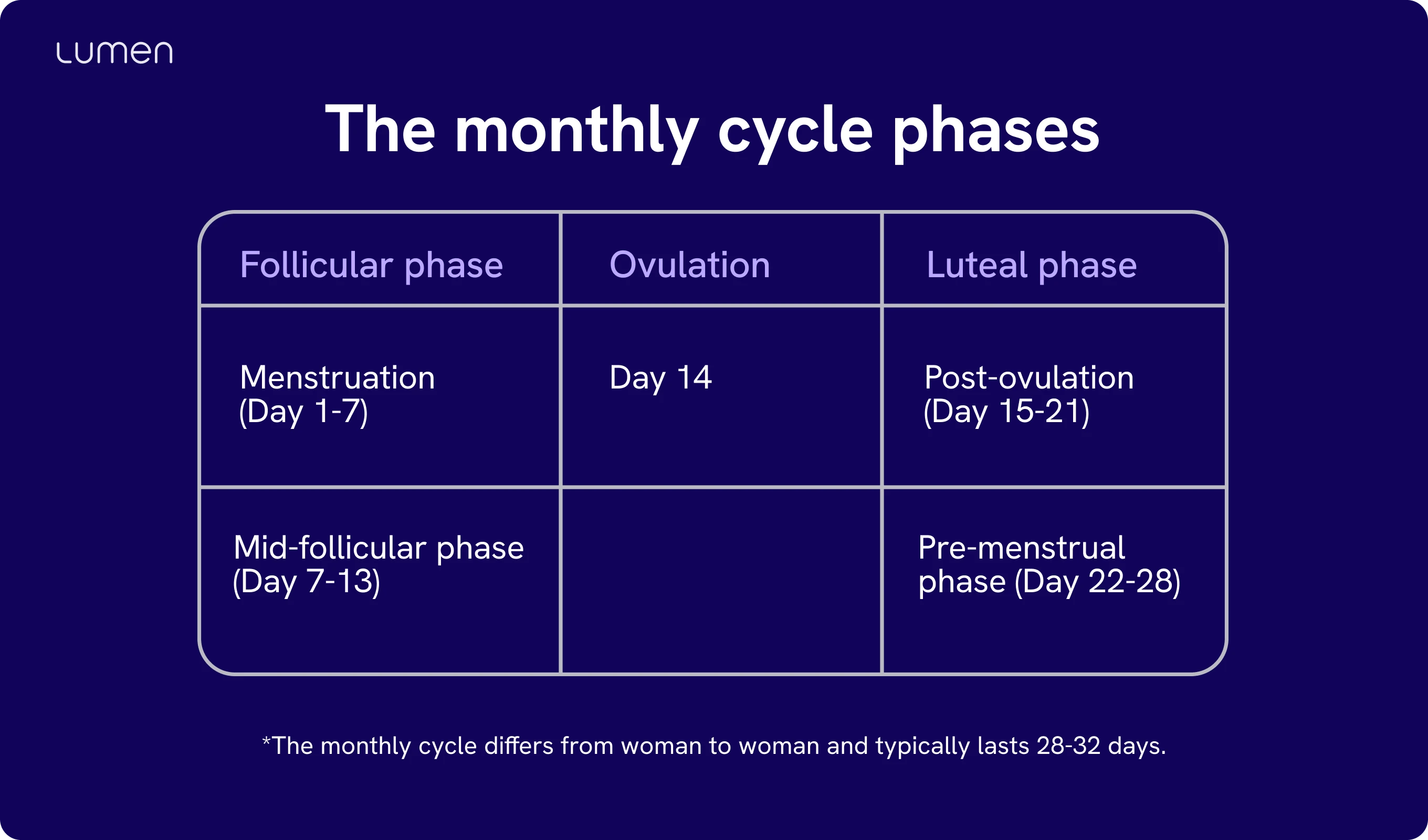

Before we discuss nutrition and fitness, it is important to understand the monthly cycle. This complex process involves the release of hormones, follicle growth in the ovaries, and shedding of the uterine lining.

Different hormonal changes and physiological responses characterize each phase.

The cycle typically lasts 28-32 days and consists of five phases:

This is the first phase of the menstrual cycle and lasts about 3-7 days. During this time, the uterus sheds its lining, which results in bleeding. Hormone levels, specifically estrogen and progesterone, are low during this phase. This means there’s no significant impact on what the mitochondria choose for fuel.

However, in this phase, you might experience higher levels of inflammation [5] and the stress hormone cortisol [6]. Because cortisol tells your mitochondria to switch to carbs for a quick power boost, you may notice your Lumen levels are higher in the menstrual phase.

Try incorporating low-intensity workouts into your day, like a walk or stretching, to alleviate menstrual cramps. Gentle exercises like yoga or walking can help soothe cramps and improve mood.

During phase two of the monthly cycle, days 7 through 13, your mitochondria are more likely to use carbs for energy [3]. During these days, progesterone is still low, while estrogen increases.

When estrogen levels increase, the body tends to rely more on carbohydrates as a primary energy source. This is partly due to estrogen’s effect on enhancing glycolysis [7], which promotes the breakdown of glucose to produce energy. You may also experience increased energy and motivation.

Now can be an excellent time to turn up the intensity of your workouts.

To take advantage of your increased energy levels, you may benefit from high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and strength training.

Carbohydrates fuel your workouts, while protein helps build and repair muscle tissue post-workout.

Ovulation is the third phase of the menstrual cycle and typically occurs around day 14. This is when the mature follicle releases an egg, which can be fertilized by sperm. During ovulation, hormone levels, especially luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), peak. During this time, the body tends to burn more carbs for fuel.

You can continue with high-intensity exercise like sprinting and weightlifting. An added perk of high-intensity workouts is that they can help your mitochondria use carbs more efficiently.

Post-ovulation is part of the luteal phase of the monthly cycle and lasts from days 15 to 21. During this phase, the follicle that releases the egg becomes the corpus luteum, which increases progesterone levels. Post-ovulation marks the start of the luteal phase and a greater propensity for fat burn.

To elevate your overall activity level, you can incorporate aerobic exercise to promote fat burning, such as walking, cycling, or light jogging.

Considering your morning levels might be lower in the luteal phase, it might be helpful to complete a pre-workout breath measurement about 30 minutes to an hour before exercise to determine if fueling up would be beneficial. This can ensure you stay in tune with what’s happening on both a metabolic and hormonal level to get the most out of your exercise sessions!

During the final phase of a woman’s monthly cycle, days 22-28, both progesterone and estrogen decrease. Lumen’s research found that CO₂ levels drop in the pre-menstruation phase, indicating increased fat burn [3].

Additionally, research has observed that carb utilization tends to be lower in the early follicular phase [10], suggesting that fat burn may increase during the late luteal phase.

Pay attention to your body. If you’re feeling tired, take the time to rest or focus your fitness on reducing stress - whether through yoga, pilates, or jogging. The more you align with your body’s needs and let it rest and recover, the better it will serve you through the other phases of your cycle.

As a woman, your menstrual cycle can affect many aspects of your life, including your metabolism. By understanding the different phases of your cycle and making simple adjustments to your diet and exercise routine, you can work in sync with your metabolism and feel your best.

Lumen’s cycle tracking leverages every cycle phase to make your metabolism work for you. You’ll find personalized recommendations for each day suited to your phase and physiology.

The information Lumen provides is for educational and informational use only. You should seek the advice of your physician or other healthcare providers with any questions regarding your health.

[1] Draper, C. F., Duisters, K., Weger, B., Chakrabarti, A., Harms, A. C., Brennan, L., Hankemeier, T., Goulet, L., Konz, T., Martin, F. P., Moco, S., & van der Greef, J. (2018). Menstrual cycle rhythmicity: metabolic patterns in healthy women. Scientific reports, 8(1), 14568. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32647-0

[2] Benton, M. J., Hutchins, A. M., & Dawes, J. J. (2020). Effect of menstrual cycle on resting metabolism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one, 15(7), e0236025. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236025

[3] Cramer, T., Yeshurun, S., & Mor, M. (2024). Changes in Exhaled Carbon Dioxide during the Menstrual Cycle and Menopause. Digital biomarkers, 8(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1159/000539126

[4] Livesey, G., & Elia, M. (1988). Estimation of energy expenditure, net carbohydrate utilization, and net fat oxidation and synthesis by indirect calorimetry: evaluation of errors with special reference to the detailed composition of fuels. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 47(4), 608–628. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/47.4.608

[5] Brown, N., Martin, D., Waldron, M., Bruinvels, G., Farrant, L., & Fairchild, R. (2023). Nutritional practices to manage menstrual cycle related symptoms: a systematic review. Nutrition research reviews, 1–24. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954422423000227

[6] Hamidovic, A., Karapetyan, K., Serdarevic, F., Choi, S. H., Eisenlohr-Moul, T., & Pinna, G. (2020). Higher Circulating Cortisol in the Follicular vs. Luteal Phase of the Menstrual Cycle: A Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in endocrinology, 11, 311. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2020.00311

[7] Rettberg, J. R., Yao, J., & Brinton, R. D. (2014). Estrogen: a master regulator of bioenergetic systems in the brain and body. Frontiers in neuroendocrinology, 35(1), 8–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.08.001

[8] Kodete, C. S., Thuraka, B., Pasupuleti, V., & Malisetty, S. (2024). Hormonal influences on skeletal muscle function in women across life stages: A systematic review. Muscles, 3(3), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.3390/muscles3030024

[9] Mlyczyńska, E., Kieżun, M., Kurowska, P., Dawid, M., Pich, K., Respekta, N., Daudon, M., Rytelewska, E., Dobrzyń, K., Kamińska, B., Kamiński, T., Smolińska, N., Dupont, J., & Rak, A. (2022). New Aspects of Corpus Luteum Regulation in Physiological and Pathological Conditions: Involvement of Adipokines and Neuropeptides. Cells, 11(6), 957. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11060957

[10] Bisdee, J. T., Garlick, P. J., & James, W. P. (1989). Metabolic changes during the menstrual cycle. The British journal of nutrition, 61(3), 641–650. https://doi.org/10.1079/bjn19890151

[11] Sacher, J., Zsido, R. G., Barth, C., Zientek, F., Rullmann, M., Luthardt, J., Patt, M., Becker, G. A., Rusjan, P., Witte, A. V., Regenthal, R., Koushik, A., Kratzsch, J., Decker, B., Jogschies, P., Villringer, A., Hesse, S., & Sabri, O. (2023). Increase in Serotonin Transporter Binding in Patients With Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder Across the Menstrual Cycle: A Case-Control Longitudinal Neuroreceptor Ligand Positron Emission Tomography Imaging Study. Biological psychiatry, 93(12), 1081–1088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2022.12.023

Brea has a Bachelor’s degree in Nutrition & a Master’s degree in Nutrition & Food from Texas Women’s University. She has been a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist for 4 years thus far. She is very passionate about uplifting others by empowering them with information regarding well-rounded nutritional intake and lifestyle practices and how they can impact overall health & wellness. She is currently a Nutritionist in the Customer Experience department at Lumen the world’s first metabolic tracking device through the breath. She has experience in a variety of nutrition-related matters, including nutrition counseling and developing community nutritional initiatives.