Master your eating times

Achieve metabolic flexibility through meal timing

Maintaining a healthy weight can be confusing, especially when so many variables seemingly lead to weight gain. Eating too late, not eating enough, overeating, or making poor nutrition choices are all habits that can affect your metabolism, sleep, workouts, and overall well-being.

Luckily, there’s a solution that goes beyond restricting carbs and calorie counting. It all starts with adjusting and mastering your eating times, which can boost your metabolic flexibility.

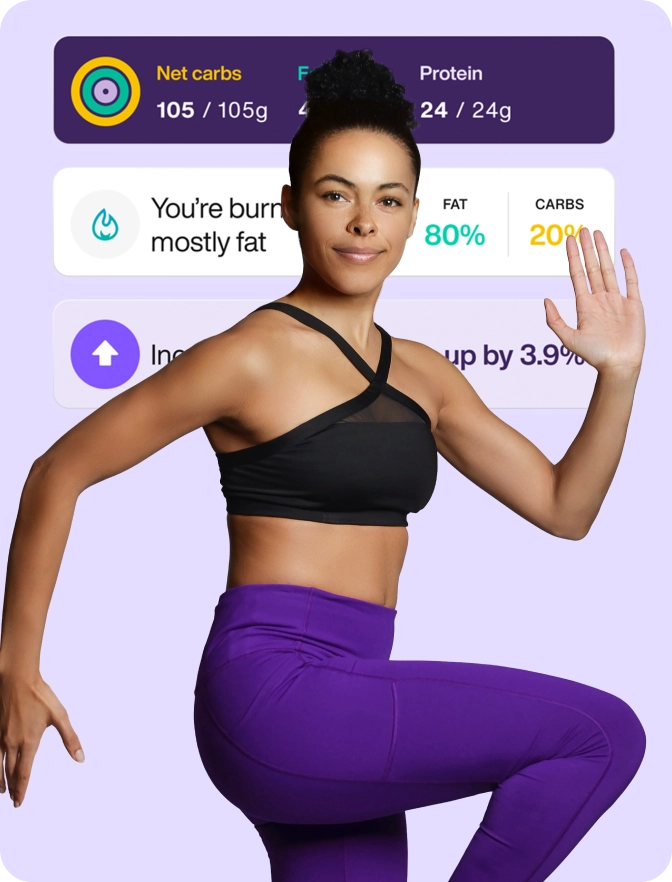

Metabolic flexibility is the ability of the mitochondria, your cells’ powerhouses, to efficiently switch between using carbohydrates and fats as fuel sources depending on their availability and your body’s energy demands.

When you’re metabolically flexible, your mitochondria can easily burn carbs for energy after carb-rich meals or during intense workouts and switch to burning fat during rest or low-intensity activities. This resilience is key to balanced energy levels, weight loss, less cravings, and improved body composition.

When to eat to boost your metabolic flexibility and well-being

Follow these practical meal-timing strategies that you can easily incorporate into your daily routine.

Eat carbs in the first half of the day

Research shows that carbohydrates are better metabolized during the day1. Eating carbs in the first half of the day helps regulate your body’s internal clock, enabling your mitochondria to transition from carb burn to fat burn overnight.

When you eat out of sync with typical light/dark cycles, it could impair satiety hormone production (i.e., leptin and ghrelin), increasing food consumption2. Leptin, released from white adipocytes, signals satiety and decreases appetite, while ghrelin stimulates appetite and fat production—leading to increased food intake and body weight. Circulating ghrelin levels are mainly regulated by nutritional status, rising with fasting and decreasing after food ingestion. This interplay between fed and fasted states shifts the mitochondria between carb and fat burn for energy.

“With the combination of metabolic feedback and daily plans, Lumen gives me a structure to work with and enables me to fuel the best for my daily requirements and consistently use the right fuel at the right time.”

Maria Fox, lost 50 lbs in 7 months with Lumen

Eat dinner earlier

Eating earlier can help prevent overnight blood sugar crashes that can wake you up. One study found that people who ate a larger breakfast and a smaller dinner lost more weight and had improved metabolic health markers3.

Late-night eating can cause your mitochondria to burn carbs overnight instead of switching to fat burn, disrupting sleep4. Syncing your eating patterns with your body’s circadian rhythm can optimize metabolic processes5 and promote weight management by encouraging your mitochondria to burn fat for fuel.

Dr. Michal Mor, Lumen’s Co-Founder, shares that Lumen users who sleep approximately 7-9 hours per night are 35% more likely to reach a fat-burn state in the morning compared to users who sleep approximately 4-6 hours per night.

Here’s how Lumen experts recommend managing your meals around bedtime for better sleep:

- Aim to finish your last meal at least 2-3 hours before bed.

- If you’re feeling hungry late at night, choose light, healthy snacks like vegetables or a small bowl of yogurt.

- Add magnesium-rich foods, like nuts, seeds, greens, and whole grains, into your diet to promote muscle relaxation and set the stage for deep sleep.

Measure your metabolism before bed and when you wake up. Your wake-up breath is the most important gauge of how your mitochondria are responding to your short-term and long-term lifestyle choices. Waking up in fat burn is the goal and means your mitochondria are efficient, since fat is the ideal fuel during rest and fasting. If you wake up in carb burn once in a while, short-term causes could be due to a late-night meal, not eating carbs earlier in the day, or illness.

“There’s a very strong correlation between food, digestion, and sleep. Eating at the right time can facilitate a night of good and restorative sleep,” says Dr. Michael Breus, sleep expert and Lumen member.

Give carb cycling a go

Carb cycling is an eating pattern that alternates between high-carb and low-carb days. It’s not a diet but rather a way of eating that helps your mitochondria to easily shift between carb and fat burn.

You can sync high-carb and low-carb days to your high-intensity training and recovery days. For example, you could eat high carb on training days to give your mitochondria the energy they need to power your workouts and replenish glycogen. You can eat low carb on rest and recovery days, enabling your mitochondria to rely on fat for fuel.

Carb cycling is preferred over long-term low-carb or keto diets. Constantly tanking glycogen stores and relying on fat for energy can make your body less efficient at using carbs, leading to quick weight gain when you eat carbs. It can also cause you to break down muscle for energy during weightlifting and increase your rate of perceived exertion due to low energy.

Try intermittent fasting

When intermittent fasting, the mitochondria shift from using glucose as a primary energy source in the fed state to glycogen, the storage form of carbs, and finally, stored body fat. This shift from carb to fat burn helps boost metabolic flexibility.

However, there is such a thing as fasting for too long. Overextending a fast can cause the body to release stress hormones, such as cortisol, in response to the perceived lack of energy intake. These stress hormones can push the mitochondria into a state of carbohydrate metabolism, where they prioritize burning carbohydrates over fats for energy. This arises from the body’s attempt to preserve fat stores if overextended fasting continues.

Finding your ideal fasting window is important for metabolic flexibility, and you can do so by measuring your metabolism throughout your fast. For example, if you measure your metabolism after 12 hours of fasting and find you’re burning fats, try extending your fast and measuring your metabolism every 1-2 hours to determine what your mitochondria are burning for energy. If you continue burning fat, this may indicate that your glycogen stores are emptying and your fast is effective. If you’ve shifted back to carb burn, then you’ve passed your fasting sweet spot. That’s a sign to end your fast and eat something nutritious.

Fuel up before and after high-intensity exercise

By strategically fueling your body before and after high-intensity exercise, you can maintain your muscle mass, enhance athletic performance, and promote recovery.

“I was learning things about my body that I hadn’t known before. I learned my body did not like carbs after 3-4 pm. This little guy [Lumen] is a game changer.”

Patricia, lost 50 lbs using Lumen

Pre-workout nutrition:

If you’re going to do a high-intensity workout, like weightlifting, HIIT, or long-distance running, measure your metabolism before to determine if you should fuel up with carbohydrates.

If you’re burning fats before weightlifting, that’s a sign to eat a high-carb snack to preserve your muscle mass.

It’s important to choose the right types of carbs. Simple carbohydrates may provide immediate energy, but complex carbohydrates offer a more steady and enduring energy supply.

Aim to eat your pre-workout meal about 1-2 hours before your workout to allow for digestion.

- Carbohydrates: Consuming a moderate amount of complex carbs before your workout can provide steady energy. Opt for options like rolled oats, whole-grain bread, fruits, or sweet potatoes.

- Protein: A small amount of protein can help support muscle repair and growth. Consider lean sources like Greek yogurt, eggs, or a protein shake.

“Before a medium-high intensity workout, fueling up with a carb-rich snack is the best way to ensure you will have enough energy for your workout.”

Marine Melamed, Registered Dietitian at Lumen

Post-workout nutrition:

After high-intensity workouts, your body enters a recovery phase, replenishing glycogen stores and repairing muscle tissue. During this time, it primarily burns carbs for energy. Once you notice a shift back toward fat burn, it’s a sign that your recovery is nearly complete. The bigger the shift to carb burn was and the longer it took to shift back to fat, the more intense your workout was.

Post-workout meals rich in carbohydrates help restore glycogen levels6, preparing the body for future activity and aiding muscle recovery. Ensuring adequate glycogen stores can enhance performance, endurance, and the body’s ability to switch between fuel sources.

Because your body is more insulin sensitive after a workout, your mitochondria can use glucose for energy more effectively and store excess carbohydrates as glycogen, ensuring quick energy production when the body needs a boost. Protein is also essential following a workout for muscle growth and repair, so consider lean protein sources like turkey or chicken on whole-grain bread with vegetables or yogurt with fruit.

Aim to consume your post-workout meal within 2 hours of your workout to optimize recovery.

- Protein: Choose lean sources like chicken, fish, or tofu.

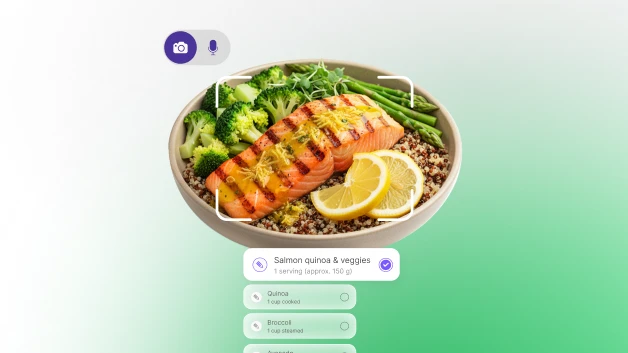

- Carbohydrates: Opt for complex carbohydrates like lentils, quinoa, squash, and brown rice.

- CoQ10: Opt for foods rich in CoQ10 to protect the mitochondria from free radicals created during an intense workout: spinach, fatty fish, nuts, and cauliflower.

- Hydration: Continue to drink water to replenish fluids lost during exercise. Dehydration can impair performance and hinder recovery.

“After medium-high intensity workouts, a high-quality carbohydrate with a source of protein could be consumed. The carbs will replenish energy stores, and the body will use protein towards muscle repair and recovery.”

Mia Johanna Dige, Metabolic Coach

Eat at regular intervals

Eating at regular intervals can prevent overeating and continuous snacking. This helps your body shift from carb burn to a fasted state in between meals, which promotes fat burn and is beneficial for weight management and metabolic health. Over-eating carbs, in particular, can overfill your glycogen stores, causing your body to store the excess as fat. At the same time, it overworks your mitochondria, causing oxidative stress that damages their membranes. Chronically high glycogen levels also make your mitochondria over-reliant on carbs, reducing their ability to burn fat effectively.

Having your meals at regular intervals also helps maintain stable blood sugar levels, improving insulin sensitivity7. Chronically low insulin sensitivity, also known as insulin resistance, is when your insulin cannot efficiently shuttle glucose from your bloodstream to your cells. This impairs energy production, making it harder for your mitochondria to shift to using glucose for energy when you need it. It can also increase your reliance on snacking for energy and lead to quick weight gain from carbs.

Master your eating times, master your metabolism

Many people are unaware of how much meal timing impacts their journey toward sustainable weight loss and a healthier lifestyle. By incorporating these strategies and using Lumen’s metabolic insights and lifestyle recommendations, you can optimize your metabolic flexibility, improve your overall health, and support your weight management goals.

Digital download

Digital download