How to speed up your metabolism to lose weight

Have you ever felt like you’re doing everything right on your weight loss journey, yet the number on the scale just won’t budge? You’re not alone.

Despite your most diligent efforts with diet and exercise, losing weight can feel like a never-ending game that leaves you feeling frustrated and unsatisfied with the results. For middle-aged women struggling with weight loss, this journey can be particularly challenging.

This is because a key element frequently overlooked in weight loss is the role of metabolism and how it changes with age.

Understanding and optimizing your metabolism as you age requires a nuanced approach that includes a balanced diet, regular physical activity, adequate sleep, and stress management.

In this article, we’ll explore how you can speed up your metabolism to shed those extra pounds and improve your metabolic health.

Metabolism is often likened to an engine that burns fuel. How much fuel this engine burns varies from person to person and can significantly impact weight loss. A higher metabolic rate means your body burns more calories, even at rest, aiding in weight loss and preventing weight gain [1]. If you have a slow metabolism, your body burns fewer calories to keep it running.

Metabolic flexibility is another critical aspect of your metabolism. It refers to how efficiently the mitochondria, your cells’ powerhouses, switch between burning carbohydrates or fats as a primary energy source [2].

Various factors can influence your metabolic rate and flexibility [3], including:

This means individual differences can impact weight loss success even with a seemingly perfect diet and exercise routine.

For example, high insulin sensitivity is crucial for metabolic flexibility because it allows your body to uptake glucose efficiently [4]. When insulin sensitivity is optimal, the body needs only a small amount of insulin. This hormone helps regulate blood sugar levels and helps glucose enter the cells to support energy production for daily activities. Insulin sensitivity also promotes glucose storage as glycogen, ensuring quick energy production when the body needs a boost.

Understanding the numerous factors affecting your metabolism can help you tailor your weight loss strategy to your body’s unique needs.

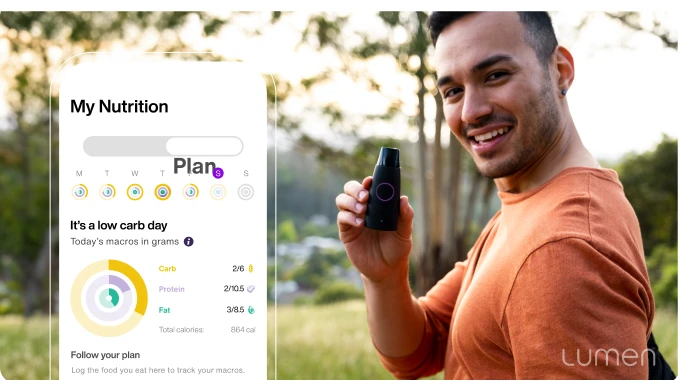

Our bodies require the right fuel to function optimally. Following a personalized macro diet means eating balanced portions of the three macronutrients, carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, based on your body’s needs. Proteins are essential for muscle repair and growth; fats are vital for hormone production and energy; and carbohydrates are the primary fuel source for your body and brain.

A macro diet emphasizes the quality and balance of nutrients to ensure your body is adequately fueled. That’s why eliminating entire food groups and extreme calorie restriction often work counterintuitively to body recomposition and weight loss efforts.

Here are some nutrition tips from Lumen’s metabolic coaches:

Eat a variety of carbohydrates (e.g., whole grains and vegetables), lean proteins (e.g., chicken, fish, and plant-based alternatives), and healthy fats (e.g., avocados and nuts).

Meal timing is another factor that can impact your metabolic rate and may also support more effortless weight loss. Eating regular meals keeps your metabolism active throughout the day. Skipping meals, especially breakfast, may slow your metabolism as your body conserves energy.

If you’re intermittent fasting, you can measure the best times to eat based on your metabolic data. By measuring your metabolic state throughout your fast, you can pinpoint the hour your body begins to enter stress mode, switching from burning fats to carbs. That indicates you should break your fast and eat something.

Lumen’s metabolic coaches recommend the following:

Start your morning with a nutritious breakfast to set the tone for the day. In the evening, smaller, lighter dinners will help you avoid the post-dinner slump.

Don’t go too long without eating—skipping meals can cause your blood sugar levels to drop, leading to overeating later.

Regular physical activity is one of the most effective ways to boost your metabolic rate, making losing weight easier. Both aerobic exercise and strength training are essential for metabolic health because different forms of exercise affect metabolism in distinct ways.

Aerobic exercise

Running, cycling, and swimming increase your heart rate and breathing, promoting cardiovascular health. Your mitochondria rely on multiple fuel sources to power your body through longer durations of moderately intense activity. Aerobically, the mitochondria primarily burn carbohydrates. However, as the intensity decreases or duration increases, as with long-distance cycling, they progressively utilize more fat as a fuel source after glycogen stores deplete. This helps enhance metabolic flexibility. In low-intensity aerobic exercises, like zone 2 walking or light jogging, the mitochondria rely on fat as an energy source.

Anaerobic exercise

Anaerobic exercise such as strength training and high-intensity interval training (HIIT), primarily use carbohydrates as a fuel source. During resistance training, muscle fibers undergo stress and microscopic damage, triggering a repair process that eventually results in muscle growth (hypertrophy). As we mentioned earlier, more muscle mass means a higher resting metabolic rate (RMR) and higher energy expenditure even when you’re not actively exercising, as muscles require more energy than fat [5]. Studies show resistance training also reduces body fat percentage [6].

Pre- and post-workout nutrition optimizes exercise performance and recovery. Glycogen, our carb stores concentrated in muscles and the liver, acts as a primary fuel source during high-intensity exercise, and consuming carbohydrates pre-workout can enhance glycogen stores [7]. Properly fueling with carbs before a high-intensity workout, like weightlifting or sprinting, can prevent muscle breakdown. The more muscle mass you gain and retain, the more mitochondria and glycogen reserves you’ll have. This means burning more fat at rest and switching to carbs when your body needs a quick burst of energy.

After exercise, your body is in recovery and repair mode. Consuming protein post-workout is crucial as it provides the amino acids necessary for muscle repair and growth [8]. Carbohydrates are also essential after exercise to replenish depleted glycogen stores.

Lumen metabolic coaches recommend these exercise tips:

Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous activity a week, plus muscle-strengthening activities on 2 or more days a week.

Adequate sleep is crucial for metabolic flexibility. Lack of sleep can lead to hormonal imbalances that increase hunger and cravings, making weight management more challenging [9].

Chronic sleep deprivation can wreak havoc on your weight loss efforts. When you don’t get enough sleep, your body produces more of the stress hormone cortisol, which can lead to reduced insulin sensitivity and promote fat storage, making it harder to lose weight [10].

Additionally, researchers recommend eating carbs earlier in the day and avoiding high-carb meals before bed, as they can cause digestive discomfort, disrupt sleep, and block morning fat burn.

Opt for a light snack or a small meal earlier in the evening for better sleep quality. Lumen users who sleep approximately 7-9 hours per night are 35% more likely to reach a fat-burn state in the morning than those who sleep approximately 4-6 hours per night.

Here are some sleep strategies from Lumen’s metabolic coaches:

Chronic stress triggers a complex hormonal response in the body, central to which is the production of cortisol in the adrenal glands.

Stress can influence the release of biochemical hormones and peptides like leptin, ghrelin, and neuropeptide Y, which can cause dysregulated hunger cues and contribute to unhealthy food choices, further hindering weight loss goals [11].

Chronic stress also leads to prolonged cortisol elevation and can lead to insulin resistance and weight gain.

Research indicates high cortisol levels are associated with fat deposition in the abdomen. Abdominal fat is particularly active hormonally and closely linked to the development of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.

These are some stress reduction techniques recommended by Lumen’s metabolic coaches to manage and reduce stress:

We’ve gathered some of the most common questions about metabolism and weight loss, and our metabolic coaches are answering them for us:

Q1: Can certain foods increase my metabolic rate?

A: While no food can dramatically change your metabolism, some can provide a small boost. For instance, spicy foods, green tea, and coffee have been shown to increase metabolic rates temporarily.

However, the most significant impact comes from a balanced diet rich in whole foods. Foods high in protein, for instance, require more energy to digest, thus increasing your metabolic rate.

Similarly, fiber-rich foods, like fruits and vegetables, increase satiety and help maintain a healthy metabolic rate.

Q2: Does metabolism significantly slow down with age?

A: Metabolism does slow down with age, primarily due to the loss of muscle mass. However, this decline isn’t as dramatic as often perceived. You can counteract this effect by staying active, eating a balanced diet, and incorporating strength training into your routine to ensure you continue building and preserving muscle.

Q3: Is a slow metabolism the reason I can’t lose weight?

A: While a slow metabolism might contribute to weight challenges, it’s rarely the sole cause. Losing weight is a whole-body approach involving diet, exercise, sleep quality, and stress management.

Speeding up your metabolism for weight loss involves more than diet and exercise; it’s a holistic approach that includes understanding and nurturing your body’s needs.

Focusing on a balanced diet rich in macronutrients, maintaining regular physical activity, ensuring quality sleep, and managing stress can significantly improve your metabolic health. Remember, the key to sustainable weight loss isn’t drastic diets or vigorous exercise regimens but a consistent, balanced lifestyle.

[1] Judge, A., & Dodd, M. S. (2020a). Metabolism. Essays in Biochemistry, 64(4), 607–647. https://doi.org/10.1042/ebc20190041

[2] Smith, R. L., Soeters, M. R., Wüst, R. C., & Houtkooper, R. H. (2018a). Metabolic flexibility as an adaptation to energy resources and requirements in health and disease. Endocrine Reviews, 39(4), 489–517. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2017-00211

[3] Martin, C. R., Preedy, V. R., & Abbatecola, A. M. (2015). Diet and nutrition in dementia and cognitive decline. Academic Press

[4] Palmer, B. F., & Clegg, D. J. (2022a). Metabolic flexibility and its impact on health outcomes. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 97(4), 761–776. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2022.01.012

[5] Kim, G., & Kim, J. H. (2020). Impact of skeletal muscle mass on metabolic health. Endocrinology and Metabolism, 35(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3803/enm.2020.35.1.1

[6] Westcott, W. L. (2012). Resistance training is medicine. Current Sports Medicine Reports, 11(4), 209–216. https://doi.org/10.1249/jsr.0b013e31825dabb8

[7] Pi, A., Villivalam, S. D., & Kang, S. (2023). The molecular mechanisms of fuel utilization during exercise. Biology, 12(11), 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology12111450

[8] Pearson, A. G., Hind, K., & Macnaughton, L. S. (2022). The impact of dietary protein supplementation on recovery from resistance exercise-induced muscle damage: A systematic review with meta-analysis. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 77(8), 767–783. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-022-01250-y

[9] Mesarwi, O., Polak, J., Jun, J., & Polotsky, V. Y. (2013). Sleep disorders and the development of insulin resistance and obesity. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, 42(3), 617–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2013.05.001

[10] Zuraikat, F. M., Laferrère, B., Cheng, B., Scaccia, S. E., Cui, Z., Aggarwal, B., Jelic, S., & St-Onge, M.-P. (2023). Chronic insufficient sleep in women impairs insulin sensitivity independent of adiposity changes: Results of a randomized trial. Diabetes Care, 47(1), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-1156

[11] Bouillon-Minois, J.-B., Trousselard, M., Thivel, D., Gordon, B. A., Schmidt, J., Moustafa, F., Oris, C., & Dutheil, F. (2021). Ghrelin as a biomarker of stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients, 13(3), 784. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13030784

_